Insurance intermediaries, beware the regulator!

The mass-market sale of affinity insurance and the rapid rise of insurtechs make the insurance industry a particularly attractive one. This is fantastic news for private equity funds, which are investing massively in brokers and other intermediaries in these days of low returns. The sanction imposed on affinity broker SFAM, which was slammed by the DGCCRF on 5 June 2019 for misleading commercial practices, serves as a reminder to managers and investors that affinity distribution practices must not ignore the rights of consumers and policyholders. The increasing number of ACPR sanctions against businesses in the sector is a clear sign that insurance remains a highly regulated area. These are two issues that will command the attention of parties to M&A transactions involving insurance intermediaries.

“These days it’s almost seen as a mistake not to have a broker in your portfolio!”(1). The rapid rise in affinity distribution of insurance products, compounded by the growth of insurtechs in recent years, has only strengthened the appetite among private equity funds for insurance intermediaries. The penalty imposed by the DGCCRF on 5 June against SFAM, the market leader in France for guarantees bundled with electronic goods, however, serves as a reminder to investors that the regulator is not willing to compromise when it comes to compliance or the protection of policyholders.

Wind of Change

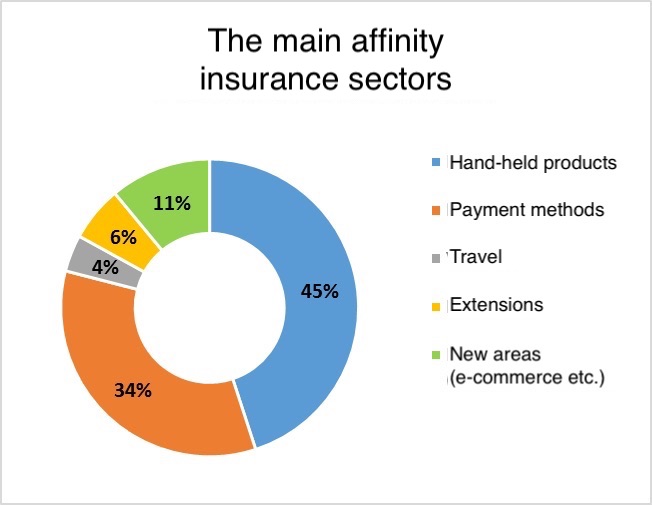

Affinity insurance distribution is defined as the sale of insurance products aimed at individuals who are members of a (more or less coherent) group. The practice first arose in connection with products intended for groups whose members had clear features in common: golfers, hunters, expatriates, practitioners within regulated professions etc. By tying in with payment cards, affinity insurance became a way to extend the sale of low-premium insurance to the mass market in the early 2000s, and has now fully penetrated mass retail channels in the form of guarantees covering domestic appliances and hand-held electronic goods. This segment now constitutes the majority of the affinity market (see below).

Breakdown of the mass affinity insurance market in France in 2017. Infographic taken from an article by Wavestone dated 6 January 2017

The affinity model has benefited substantially from the ever-increasing sophistication – and hence the price – of electronic goods, in particular smartphones. And while the price of an iPhone passed the symbolic milestone of €1,000 in 2017, paying another ten euros or so for a guarantee to go with it now seems like a rational thing to do. Especially in view of the fact that the sturdiness of mobile phones has not increased as quickly as the cost. Players such as April, the Société française d’assurance multimédia (French multimedia insurance company – SFAM), Gras Savoye Willis and Orange Courtage have clearly understood this. The creation in 2012 of the Fédération des garanties et assurances affinitaires (Federation of affinity guarantees and insurance – FG2A) by a group of brokers, insurers and distributors clearly illustrates the success of the affinity business model.

Having become a broker in its own right in 2010, SFAM has seen dizzying growth of 2,400% over the last five years. For many professionals in the sector, these figures are a clear demonstration that the future belongs to the affinity model – having achieved turnover of €50 million in 2015, €135 million in 2016 and €250 million in 2017, SFAM posted revenue of €500 million in 2018 and was anticipating €740 million at the start of June 2019.

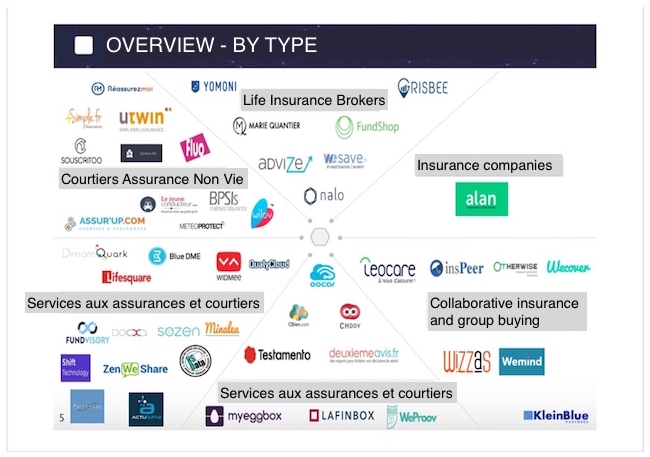

Another source of growth in the insurance sector is the increase in the number and range of “insurtechs” – fintechs that specialise in insurance (see chart below), which for the most part are insurance intermediaries (2).

It is a sign of the times that the number of incubators aimed at supporting start-ups in the insurance sector has been rising in recent years. AXA set up its incubator Kamet in 2015, and in 2016 CNP launched its Open CNP funding programme, with a budget of €100 million over 5 years. More recently, the major mutual insurers(3) expressed their desire to promote socially responsible innovation via the incubator French AssurTech, based in Niort (February 2018), and the French Insurance Federation (FFA) launched the Hub in the autumn of 2018. This is an incubator that offers regulatory advice to start-ups and puts entrepreneurs in direct contact with the various insurers to enable them to seek financing. In early July 2019, L’Argus, which counts as required reading in the insurance sector, held its second Argus Factory – a trade fair dedicated to transforming the industry.

Infographic produced by Klein Blue in its Overview of Insurtech in France 2017. The innovation consultancy goes beyond simply listing market players to emphasise the diversification going on within the sector.

Private equity snaps up brokers

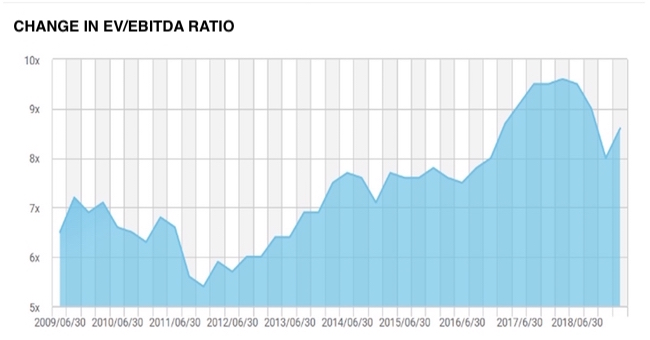

With the rise in affinity distribution on the one hand, and the dynamism of insurtechs on the other, it is only to be expected that insurance intermediaries are attracting the attention of investors. Unlisted funds are keener than ever on these brokers, given that they tick all the boxes needed for a successful LBO – cash flow is generated by collecting premiums, which is reassuring for creditors and makes it possible to finance deals with a high proportion of senior debt, margins and hence profitability are substantial, and above all the business is recurring in nature, which makes it possible to broadly forecast a broker’s turnover from one year to the next and helps to reassure investors. For all these reasons, insurance intermediaries fall within the upper range of valuations, with an EBITDA multiple generally between 9 and 15.

All the stars seem to be aligned for players in the brokerage industry, who are thus able to finance their growth by selling equity interests to private equity funds at very high prices.

In return, the funds are able to realise attractive gains that attract investors to the unlisted sector – and most insurance intermediaries fall within this category. The appeal of this alternative investment model, which does not involve the liquidity seen on the financial markets, can be explained by the excess liquidity that is available as a result of the expansionary monetary policies implemented by central banks after 2008 (in particular “quantitative easing”). Interest rates are zero – or even negative in the case of certain government bonds – which encourages holders of capital to move away from traditional investment channels in search of returns in the field of private equity.

There is also a sociological factor that has a tendency to reinforce growth in the brokerage industry, one which developed in France in the 1980s with the financialisation of the economy, often driven by independent entrepreneurs who are now seeking to realise their capital. This partly explains the fact that investor demand is effectively met by the supply provided by brokers, who are willing to sell a stake in their business.

The equation is set in the same terms for insurtechs, which benefit from the explosion in the number of venture capital funds, some of which are willing to get involved with entrepreneurs at an increasingly stage (business angels, seed or early stage financing). Above all, insurers are interested in insurtechs’ strength. For those who are sometimes identified as having “technological debt”, the temptation to make up for lost time by entering the venture capital race is great. The role of corporate VCs in financing innovation should also be highlighted, as demonstrated by the amounts committed by Maif Avenir (€250 million) and Axa Venture Partners (launched in 2015, €425 million under management).

Graph produced by the research firm Infront Analytics showing the upward trend in the EV/EBITDA ratio, a very widely used tool for valuing unlisted companies. It is not uncommon for brokers to be purchased for a price of up to 15 times EBITDA.

“You have to be ultra-clean”

The pitfall would be to forget that the insurance sector is receiving a great deal of attention from the regulator. The transposition of EU Directives IMD(4) and IMD 2(5) into national law, as well as increasing regulation in relation to combating money laundering and terrorist financing (“AML-CFT”) are the most telling examples of this. The number and scale of sanctions issued by the French Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority (ACPR) has been increasing since its creation in 2010.

The current political climate calls for strict compliance with AML-CFT rules. Thus the €8 million penalty imposed on the broker SPB in the decision of 26 July 2018 was due to deficiencies in its AML-CFT system that were deemed to be “significant”. These are recent regulations, and compliance with them can sometimes represent a sizeable investment for small players or ancillary intermediaries(6), as is the case for many consulting firms that offer insurance in addition to their services. Even so, such firms are spared little of the regulatory burden, and must implement almost all the regulations set out in the numerous guidelines regularly published by the ACPR.

It is therefore easy to understand the scale of the challenges faced by new intermediaries when it comes to regulatory compliance, especially in connection with private equity. This is because investment funds increasingly take into account a target’s level of compliance when calculating its financial value – “You have to be ultra-clean!”(7)

Minimum compliance

Insurance intermediaries cannot overlook the rights of consumers, which are afforded a particularly high degree of protection under French law. The principle established by case law (Court of Cassation, 2nd Civil Division, 01/06/2011, 09-72.552 10-10.843)(8), under which any doubt as to the interpretation of clauses within insurance contracts is resolved in favour of the policyholder, is a clear illustration of this bias, which considerably extends the consumer’s options for cancelling or withdrawing from a contract(9). In the decision of 18 May 2017, the Banque Postale was fined €5 million in its capacity as an intermediary. The ACPR criticised it for shortcomings in its systems for informing customers where certain life insurance products were subject to excessive losses.

Because it is essentially based on a B2C model, affinity insurance presents an increased risk arising from unfamiliarity with consumer law. On 5 June, the General Directorate for Fraud Control (DGCCRF) penalised SFAM for “misleading commercial practices”, as part of a €10 million criminal case (10). The Fraud Control Directorate accused the broker of using bonus-driven selling practices that were likely to mislead consumers. The disputed contracts were issued in Fnac-Darty shops by SFAM employees and were often presented as discounts on the insured product (phone, headphones etc.). As a result, many customers took out insurance without realising they had done so, only finding out when the monthly premium was debited to their account. In addition, consumer associations highlighted the large number of exclusions included in the contracts which, in their view, meant they were of limited use, as well as pointing out that it was very difficult for customers to cancel the contracts in question when they contacted SFAM’s customer service department. UFC-Que Choisir raised the complaint against SFAM and Fnac in August 2018. The particular factors cited as being the source of the problem were the generous bonuses, which amounted to €5.50 per contract taken out for Fnac employees (versus €1 or €2 more generally), pressure from management and the retail staff’s lack of training on insurance – which can be interpreted as a breach of the obligation to provide pre-contractual information (11), a principle which the regulator is very sensitive about when it comes to insurance contracts. Some people saw a potential conflict of interest as a result of SFAM’s acquisition of a stake in Fnac-Darty in February 2018. The company owns 11% of the group, making it the second largest shareholder. Lastly, it should be noted that the DGCCRF – in the first sanction of its kind – required SFAM to reimburse the consumers affected.

The ACPR ultimately questioned the usefulness of certain affinity contracts in a publication from October 2018, referring to the criticisms made by consumer protection associations that the guarantees provided are often already covered by most comprehensive home insurance policies or by the legal guarantee of conformity(12).

In conclusion, compliance and adherence to consumer law have become key issues for brokers and hence indirectly also for investment funds. And while the future looks promising for an industry which is undergoing a major transformation, it has become essential to be fully conversant with insurance law and practice in order to make the most of all the opportunities it brings for companies and investors. Compliance is also likely to become an unavoidable issue in negotiations about the valuation of this type of insurance intermediary.

Jérôme Goy

______________

Sources:

(1) Jean-Louis Duverney Guichard, M&A Partner at EY, 13 September 2018 in L’Argus de l’assurance

(2) Within the meaning of Article L511-1 of the French Insurance Code

(3) GROUPAMA CA, IMA, MAAF, MACIF et MAIF

(4) Law of 15 December 2005 setting out various provisions for adapting to Community law in the field of insurance and Decree of 30 August 2006 relating to insurance mediation and amending the Insurance Code (regulatory section) in the context of the transposition of the EU Directive of 9 December 2002 into national law

(5) Order of 16 May 2018 and Decree of 1 June 2018 relating to the distribution of insurance, in the context of the transposition of the EU Directive of 20 January 2016 into national law

(6) Within the meaning of Article L511-1 of the French Insurance Code

(7) David Salabi, founding partner of merchant bank Cambon Partners, quoted by L’Argus in an article dated 7 September 2017

(8) On the basis of Article L133-2 of the French Consumer Code

(9) In particular, by giving the policyholder the option to cancel comprehensive home insurance and motor insurance policies at a date of the policyholder’s choosing, and the option to change mortgage insurance providers for a period of one year after signing the agreement, while at the same time preventing the lender from charging a fee

(10) Process established by the “Taubira” law of 15 August 2014 (relating to individualised sentencing and increasing the effectiveness of criminal sanctions) and the implementing decree of 13 October 2015

(11) Established by Article 1112-1 of the French Civil Code

(12) Established by Article L217-4 of the French Consumer Code